A while ago I mentioned that I would put up a

post on paper sizes.

Paper size and how to express it is a

complex set of issues. For instance, when setting out sizes, in order to

indicate the grain direction it is common to put the edge that goes alongside

the direction of the grain last. E.g. 17×11 inches is short grain paper and 11×17

inches is long grain paper, alternatively the grain alignment can be indicated

with an underline (11×17 is short grain) or the letter "M" for

"machine" (11M×17 is short grain). Grain is important because paper

will crack if folded across the grain: for example, if a sheet 17×11 inches is

to be folded to divide the sheet into two 8.5×11 halves, then the grain will be

along the 11-inch side. Paper intended to be fed into a machine that will bend

the paper around rollers, such as a printing press or photocopier should be fed

grain side first so that the axis of the rollers is along the grain. All good

print companies will be able to advise on this, but you will sometimes want to

use print machinery yourself and having an idea about how grain direction will

effect the final outcome, allows you to have a better control over how you are

working.

The Wikipedia entry on paper sizes is

extensive and useful, so I will not go over the same ground. However it is

perhaps useful for you to note how paper sizes change over time and that these

changes are often to do with wider political or economic factors and that the changes

made can subtly effect the way we think about size, shape and meaning.

When I started art college in the late 60s

the standard paper size for drawing was Imperial; 22 x 30 inches. Now we tend

to use A1 which is 23.4 × 33.1, however the extra inch and a half on the width

is important because it changes the way that we carry paper around. An Imperial

portfolio would just fit under a man’s arm (and some women’s), your fingers

could support the bottom of the portfolio, but now they are bigger, they have

to be carried by a handle. A subtle difference, but one that reflects a deep

divide between old and new units of measurement. Old units tend to be taken

from the body and averaged out. You can measure a horse in hands or a length of

cloth in feet. A cubit was the length from finger-tip to elbow, an inch was in

many languages related to the thumb. E.g. Catalan: polzada inch, polze thumb; French: pouce

inch/thumb; Italian:

pollice inch/thumb; Spanish: pulgada

inch, pulgar thumb; Portuguese: polegada

inch, polegar thumb; Dutch: duim

inch/thumb; Afrikaans:

duim inch/thumb; Swedish:

tum inch, Danish and Norwegian:

tomme / tommer inch/inches and tommel thumb, tumme

thumb; Czech:

palec inch/thumb; Slovak:

palec inch/thumb; Hungarian: hüvelyk

inch/thumb. The Scottish inch was the width of an average man's thumb at the

base of the nail.

An Anglo-Saxon unit of length was the

barleycorn. After the Norman invasion in 1066, the inch was incorporated into

law, it was defined as equal to 3 barleycorn, which continued to be its legal

definition for several centuries, with the barleycorn being the base unit. One

of the earliest such definitions is that of 1324, where the legal definition of

the inch was set out in a statute of Edward II, defining it as "three

grains of barley, dry and round, placed end to end, lengthwise".

The foot has been used in England for over a

thousand years. The foot, a length of the human foot, was anything from 9 3/4

to 19 inches. However it was not until 1844 that the standard we now use was defined.

A yard is based on a single stride. Henry I

(1100-1135) decreed the lawful yard to be the distance between the tip of his

nose and the end of his thumb.

Fathoms measure depth of water. They have been in use

in England since before 1600, and derived from faethm, the Anglo Saxon

word for 'to embrace' because it is roughly the distance from one hand to the

other if your arms are out-stretched.

Units of measurement always used to be

related to things that common people would understand, this is very different

to the metre. A commission organised by the French Academy of Sciences and

charged with determining a single scale for all measures, advised the adoption

of a decimal system and suggested a basic unit of length equal to one

ten-millionth of the distance between the North Pole and the Equator to be

called mètre ("measure") (19 March 1791). The first occurrence

of metre in this sense in English dates to 1797. This rational system

would gradually replace all others, but in doing so it would also sever the

links between measurement and common experience.

The reason Imperial had become the standard

size for drawing was simply that it was the largest size that could be carried

flat under the arm. A1 is slightly too big and A2 seems ‘mean’ in comparison to

Imperial, so we adapt and work around something that no longer feels natural. I

can no longer ‘embrace’ the paper under my arm.

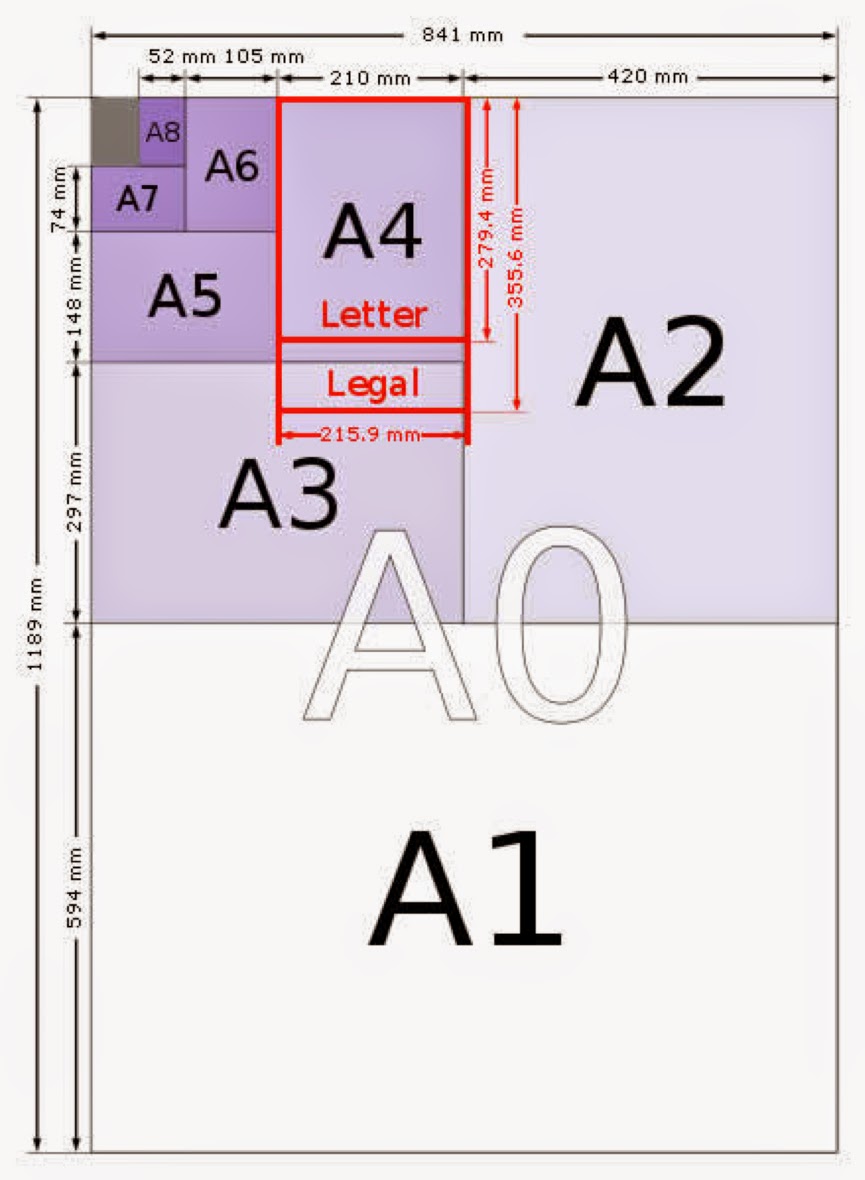

The fact is that A1 dimensions are

mathematically ‘perfect’, i.e. they are always half the size of a sheet of A0

paper when cut through the longer length. The base A0 size of paper is defined

as having an area of 1 m2. Rounded to the nearest millimetre, the A0

paper size is 841 by 1,189 millimetres (33.1 in × 46.8 in).

The significant advantage of this system is

its scaling: if a sheet with an aspect ratio of square root of 2 is divided into two equal halves parallel to

its shortest sides, then the halves will again have an aspect ratio of square root of 2 . Good for business as printing

companies will have much less waste, but perhaps not so good for artists who might want a more ‘personal’ relationship with paper size.

Working out weight to paper size, when using the

metric system, is reasonably straightforward. This calculator will help you. Grammage,

is defined as weight in grams of one sheet of paper that is one square

metre in area. It is sometimes easy to

forget how heavy paper is when you just use single sheets, but when deliveries

are made we often take paper in by packs of 500 (a ream) and these are seriously heavy. For some reason when ordering printing papers reams are often 516.

Another anomaly when looking at paper sizes

is that of newspaper sizes. If you look at the table below, you will see that

despite the introduction of ISO standards, the newspaper tabloid still

maintains a size based on a particular nation's traditional measures.

It’s

interesting that paper bags were first measured by how many pounds of sugar

they could hold.

In the USA paper grocery bags now come in a variety of

paper weights from light (30 lb.) to heavy-duty (70 lb.) and 14 stock sizes,

capable of holding 2 to 25 pounds.

If you

want to use paper bags to draw on, it costs only £3.49 for 1,000 5x5 inches white ones. (Price checked on the day of this

post).

Perhaps you could begin to

respond to these issues by building a set of personal measures. For instance a

yard could be determined by measuring the distance from your nose to fingertip, with arm straight out to side, head facing front.

This is a very useful way to measure rope and fabric. The thumb could be measured or a finger or

half finger. The palm of the hand or the hand span is another good place to

start, lengths could then be used to calculate surface area. A body surface area calculator exists here: you might find it useful to think about how much area your skin would take up if unfurled and laid out flat like paper.

Once a paper size or shape is decided on you could

think about how measures work in terms of other trades. Find a link here.

For instance Mohs scale of hardness could

be used to check on your art materials relative hardness or softness. As it is

basically a test done by rubbing one surface against another and seeing which

one is ‘rubbed off’, you could think about testing your papers and drawing materials in this way too. Graphite rubs

off on paper, so paper must be harder.

So what could you use to

determine paper size? Could it relate to the room you make your work in, should

its proportions echo those of a particular set of proportions you have researched and found belonging to an object or site that has a poetic significance? Should your paper size relate directly to your own body? What should it reference? Mathematical certainty, such as the Golden Section or found association, such as being exactly the same size and colour as a post-it note left on a fridge door that said 'WE NEED MILK'. One of the ways you can work as an artist is to find connections and significance between things and the more surprising these are the more intriguing the work can become.

See also:

Mathematics and metaphor

Research into paper