In Richard Cytowic's 'The Man Who Tasted Shapes' it is pointed out that no two synesthetics 'see' their associations the same way, one person hearing the sound of a trumpet as bright red, another as cold blue. These issues point to a much more complex problem and one fundamental to my question. Are languages learnt or innate? We can all agree that a banana is yellow, but have we come to that agreement because we have learnt this, or because we have perceived this? Colour theory points to the fact that colour is dependant on the light source. During the day the predominant colour of daylight can shift, things should appear bluer in the morning and redder towards twilight, but whenever we look we still see a white piece of paper as white, we don't notice that appearances remain constant under widely different conditions, because it is useful for us to believe that the same essential thing still holds 'true' form or shape. If every time we saw something it changed, we would spend too much energy trying to decide whether or not it had now become a threat. Scientists have named this psychophysical issue 'colour constancy'. We in effect attribute a constant colour to things seen, 'one different from what it 'really' is'. (Cytowic, 2003, p.62) Cytowic goes on to state; 'The flux of energy reaching our retinas changes constantly. The same is true for the flux reaching our other sense organs. Since our sense organs are energy transducers, our perception of what things "really" are should change accordingly. Instead we are confounded by an illusion of constancy where non "really" exists'. Therefore the question about visual language should perhaps be rephrased as, 'How do any of us agree on anything?'

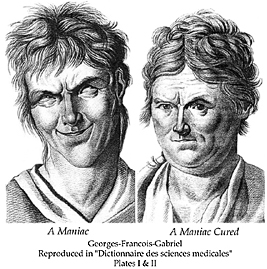

I found this interesting diagram of synesthesia. It points to a complex interdependence of sensory information and to the development of meaning through association.

What is important to us is partly learnt and partly innate. We feel hunger, but cultural coding will depend on how we satisfy it. In India it is unlikely that you will be able to eat a cow to satisfy your hunger, but in Argentina it is hard to be a vegetarian. However it is of course possible that someone could eat beef in India and a salad in Argentina, but in each case they would be seen to be 'transgressive' of what is regarded as a 'norm'. I would suggest that 'visual language' is similar to this. We learn British road signs and associated conventions because these are essential to our well being. If we step off the pavement and look the wrong way for traffic we could be killed. However we have to re-learn traffic direction conventions if we travel outside of the British road sign 'language' limits. You could therefore regard art college training as simply learning to read the 'art' road signs. The problem being that no one has a definitive highway code.

The issue of language 'rules' is perhaps like so many things eventually a political one. Who gets to determine the rules of language and how? When the Normans invaded and conquered England they imposed French as the language of discourse, only 'common' people spoke 'English', or what was then seen as 'English'. Gradually of course the courtly French language would merge with old English, to form the language we now use. However the 'English' we use is constantly changing and certain constraints are put in place to ensure it doesn't change too quickly, for instance the Oxford English Dictionary will only allow a new word to be recorded in the dictionary after serious research that has established a new word's common awareness amongst a wide range of people and a proven use value. (I.e. the new word is needed, because it allows things to be said, and of course therefore thought, that older combinations of words are unable to articulate correctly.) So languages do change, but they keep their shape by regulation and the regulators are by definition powerful.

Young children need to be brought into the social matrix by education into basic rules of behaviour, and one key aspect of this is learning the language of the 'tribe', in our case 'English'. However verbal language is only one aspect of this learning, another is the constancy of identification in relation to formal change. By feeling an object at the same time that it is looked at, a child can determine that although it looks very different from different angles, it still has one identity. This is reinforced by social behaviour, others pointing to said object and giving it a name, and doing this over and over again, until several 'associations' are made and it is these inter-related associations that begin to ground meaning. This process is very sophisticated and will eventually allow us to be able to read both red and green apples as 'apples'. We learn to decide whether form is more important than surface colour, or weight more important than texture, constantly testing out the world in association with the 'rules' we are taught.

If I take this analogy back into art education you can clearly see how at interview to a BA program some students are taught how to shape their practice to fulfil the language of 'A' level art and others the language of their foundation course, we of course as a degree programme are continuing the practice, but it can be hard to see the rules when you are a fish swimming in the waters of the institution.

It is however no different outside of the education world. The 'art world' itself has languages of discourse and you have to become an insider to learn these rules.

Therefore you could argue that this blog is itself a means to introduce you to the 'rules of the game'.

For instance the blog covers several overlapping areas of accepted 'language' use.

It establishes old patterns of language, such as the fact that there is a 'specificity' to the way each material can be handled, so posts looking at 'graphite' or 'ballpoint' it could be argued reinforce ideas initially brought into aesthetics by Lessing and then elaborated by Greenberg. Posts on more performative aspects of drawing point to an expanded practice of drawing (and art) and the fact that performative theory is now one of the key areas of art's theoretical investigation, as it allows us to see 'art' in relation to all areas of human activity, and the processes of human interaction, rather than just in relation to the symbolic meaning of static objects.

By moving from subject to subject, and yet at the same time each post being about 'drawing' this blog provides a similar learning curve to the one you go through when trying to work out whether the changing forms of an object are all part of one thing or whether new things are forming. As Father Ted argued, a cow is still a cow, even if it is tiny and in the distance. It is experience and association that will allow us to eventually realise that as one aspect of use is mastered, we may well have to reconcile this with new uses. We can still appreciate a drawing that explores material properties or provides us with a visual narrative, whilst also being able to appreciate a drawing that is performed or is about process rather than being an object for contemplation.

The complexity of the situation is actually what makes it exciting.

The artist James Merry has synesthesia. This is what he has to say about his recent embroidery work, “I think a lot of it was an attempt to explain actual physical sensations I would feel when looking at plants or flowers—some kind of weird tactile/plant synesthesia. My fingers would tingle when I'd see small furry buds on the end of branches, or I'd feel flowers growing out of my eyes if I stared at them too long. I was fascinated by that overlap between botanical and anatomical. It's always such a lush place, where two seemingly different worlds can overlap”.

This drawing (below) by James Merry was an attempt by him to illustrate how he has an awareness of his own particular synaesthesia. The drawing tries to show how his own awareness of his 'optic nerves' can be as much about the physical presence of these things in his head, as an 'outside' view.

Merry is a long time collaborator with the musician Bjork, another artist who is concerned to break down the barriers between art forms and to 'realise' the power of music to effect our emotional/physical experience. She believes that her ideas can be further developed when coupled with other art forms and by working with other artists. What I was particularly interested in was that Merry's synaesthesia allowed him to 'read' what we would simply see as a language of the logo, as something much more sensual. For an artist all things are potential fertile ground for the growth of creative ideas.

See also:

http://fineartdrawinglca.blogspot.co.uk/2014/08/eye-music.html

http://www.epistemocritique.org/spip.php?article296&lang=fr

http://i-d.vice.com/en_us/article/bjork-collaborator-james-merrys-incredible-embroidery-creations?utm_source=idfbuk

http://www.epistemocritique.org/spip.php?article296&lang=fr

http://i-d.vice.com/en_us/article/bjork-collaborator-james-merrys-incredible-embroidery-creations?utm_source=idfbuk